I can open my Bible to Psalm 37 in the dark. It’s because I stained the pages with tears six years ago, and now, as if in memorial to what the Psalm did for me then, their wrinkles remain, like capillaries in the sand left by a dried river. I can feel my way to the center of my Bible, to the bumpy pages of that psalm.

If my freshman year in college had presented intellectual challenges to my belief in God, my junior year settled the balance in emotional challenges. After a months-long ordeal with a roommate who was abusive and manipulative, I struggled to find my footing. I lost interest in praying and writing and singing at church. God seemed to have forgotten me; it seemed like He would never help me. That became the prayer I prayed when I could pray: Help me. Help me. Help me. But when I prayed for help, I sank deeper into despair.

What I believed about God had been ripped out from under me. Was God really good to me on a personal, day-to-day level? My experience seemed to have proven otherwise, as much as I wanted and looked for evidence elsewhere. Now, no longer certain of his care for me, I became afraid of him. I no longer knew God as my faithful, loving Father. I was forgotten, unwanted, unseen, and—the one that hurt the most—unloved. Perhaps, if I got face-to-face with him, he would tell me, like so many people did, that I needed to be grateful it was over and get my act together. Perhaps he would say I was weak and faithless, which I already knew was true anyway. But I also wanted him to step down and hold my hand or speak to me with tenderness like my third-grade teacher used to or just tell me that it was OK to mourn, to tell me that I didn’t have to be afraid, to show me that he really was gentle and compassionate.

But nothing happened. I began to feel ashamed of my lack of faith, of my inability to press in to God, of my inability or unwillingness or—whatever it was, God help me!—to muster up the will to keep going. Sorrow multiplied.

There were times when I wished that I didn’t believe in God, but after a serious period of questioning my freshman year of college, I had firm intellectual conviction that Christianity was true, at least on paper. But now my faith became a burden, another failed expectation. How could I believe that God was good? How could I struggle with that belief but still be a Christian? How could I possibly grapple with the fact that God sent his Son to die for me on the cross but at the same time let me be so wounded?

It would have been easier to believe that God had simply made a mistake. Perhaps he had forgotten about me, or perhaps he overestimated my strength, giving me a temptation that was, in fact, more than I could bear, or perhaps he simply cared about me less than I thought he did. But I couldn’t find any evidence for these things in the Bible.

My theology was at war with my personal experience, and I was at war with myself. How could I get at the truth? What was the truth? Perhaps I was raging at God. Perhaps I was prideful about what my life should look like or what God’s love was supposed to look like. But underneath the louder emotions was the true one: I was hurting, badly, and afraid that for some reason, God did not love me any longer.

One evening early on in my senior year, I sat in my living room in my new apartment, where I lived alone. I finally had a place of rest to call home, a place where I was, finally, safe. Everything was still. Everything was quiet. For the first time in months, I felt the flicker of peace in my soul.

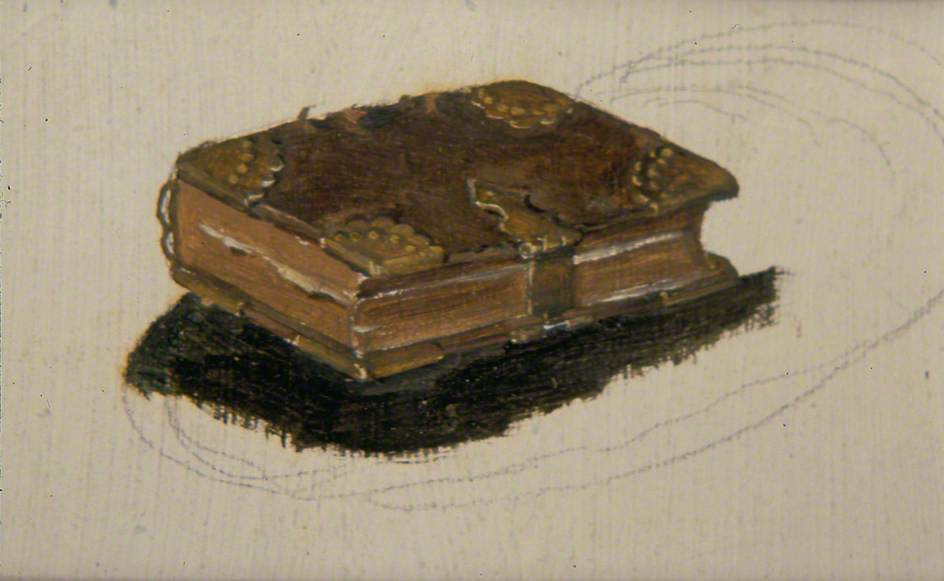

Perhaps in an act of defiance or even hope, I had brought my Bible with me when I moved. It remained untouched on my TV stand. I looked at it with disinterest. When one no longer believes that the God who wrote the Bible is good, it makes the whole Bible a lot less compelling.

But then I paused.

I didn’t like living in enmity with God. And if the Bible was true, there had to be more than my personal experience. There had to be more going on. There had to be a way out. God had to help me. If the Bible was true, God still loved me, even if I didn’t think he did anymore. He wouldn’t be bound by my unbelief.

I had been afraid to seek God. I was afraid that he would keep being silent, and I’d rather the reason for his silence be that I stopped asking too soon than that he kept ignoring me. But maybe there was goodness left for me, maybe there was love or kindness or something smaller that might help me keep going. Perhaps, like Jacob wrestling with God, I was stubbornly insisting that God meet me where I was—and perhaps the willingness to wrestle, to take up my Bible at all, meant that somehow, somewhere, some faith remained (Genesis 32:22-32).

I looked at the Bible again. “God, help me.” My prayer of the last few months, henceforth unanswered, but worth uttering one more time. I set the Bible in my lap. It felt like a brick. Psalm 37 came to my mind. It was a distant memory; I no longer remembered what it said. I don’t know where the passage came from; perhaps God simply brought it to my mind.

Fret not yourself because of evildoers;

be not envious of wrongdoers.

For they will soon fade like the grass

and wither like the green herb. Psalm 37:1-2

My attention was immediately arrested. And then I read the penultimate verse:

The salvation of the righteous is from the Lord;

he is their stronghold in the time of trouble. Psalm 37:39

I repeated it to myself: “He is their stronghold in the time of trouble.” The time of trouble had come. But had God been my stronghold? Memories of the months before flooded in. Was God with me as I attended classes dreading going back to my apartment? Was he there as I locked my bedroom door and put my chair underneath it? What about when I stayed in my friends’ homes to get a few hours of sleep? He did, I realize, at least give me those faithful friends. He had provided this new place for me to live by myself.

And if he did those things, perhaps God was with me when I questioned him, when I wept to him, when I prayed until I could muster only a whimper, and when I choose to be silent, as if I could block him out. The psalm told me that God “upholds the righteous” and that “though [the righteous man] fall, he shall not be cast headlong, for the Lord upholds his hand” (Psalm 37:17; 24). I had fallen, that was true—but falling didn’t mean God wasn’t with me. Was he upholding my hand, even now, through this psalm?

If he was, then I had something in addition to my sorrow. I had a God who reached down and gave me the words I needed; I had a God who saw me in my mess and sadness and grief and reached down and saved me. Psalm 37 was what I needed. It gave me the truths my soul needed to hear. Did that mean that God was here?

By the time I finished reading, the pages of the psalm were soaked. I laid the Bible on the kitchen countertop to dry. It was finally open. And now, as the pages took time to dry, it would need to stay open. The pages would be wrinkled, but they, at last, had been read. I had the answer to the question I had been earnestly asking: Did God still love me? Yes, he did.

I don’t know why God lets bad things happen to me or you or anyone else. I tend to find theodicies—philosophical explanations for why evil exists when God is all-powerful and good—intellectually convincing and existentially unsatisfying. But we, as Christians, have so much more than a sound theodicy to sustain us in times of sorrow. Martyn Lloyd Jones once wrote,

You may not have a full explanation…but you will know for certain that God is not unconcerned. That is impossible. The One who has done the greatest thing of all for you, must be concerned about you in everything, and though the clouds are thick and you cannot see His face, know He is there…1

When I no longer had the courage to ask God my deepest question—Do you still love me?—he did not simply respond yes, but held me in his arms. He showed me that he was there, and it was his presence that convinced me of His love for me again. It was not on my timeframe, but it was good and holy, and it saved me.

Now, I can open to Psalm 37 in the dark, but I am grateful that the Psalm itself has become an anchor in my life that staves off the darkness. It pushes back the deepest sorrow, the feeling that one is unseen or unloved by God, the feeling that sometimes slides into belief. It reminds me that there are realities greater than our suffering because our suffering will one day end.

In 1 Corinthians, Paul writes that “So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love” (1 Corinthians 13:13). I’ve wondered, at times, why is love the greatest. Now I think it’s because it is the most eternal, if eternality can be measured. Faith will one day turn into sight. Our hope in Christ will be fulfilled. But our love for Christ will never end. In fact, it is only beginning—because we, too, are only just beginning to grasp the depths of his love for each of us. He loves us as we stare at our Bibles without the strength to open them; he loves us as we grieve what he has allowed in our lives; he loves us even—especially?—as we weep into his Word. He does not tire of the question, “God, do you still love me?” from the weary or broken. His answer is—and forever will be—yes.

–

About the author.

© Olivia Davis 2023, all rights reserved

Leave a Reply