Jesus offers us compassion. Many of us understand this on an intellectual level, which is a good thing—it is important to know that Jesus is compassionate. But perhaps that intellectual understanding is just the beginning of letting our lives and hearts be shaped by the compassion that Christ shows us. He wants us to experience his compassion, to let that knowledge of who he give us the confidence to approach him when we need help. Looking at Jesus’s earthly ministry and the way that people responded to him when they needed compassion can help us begin to anchor this truth in our hearts as strongly as it is in our minds.

A Compassionate High Priest

Compassion is an essential part of who Jesus is. In Hebrews, the one qualification of the role of the high priests in ancient Israel is compassion. As verse 5:2 reads, the high priest “can deal gently with the ignorant and wayward, since he himself is beset with weakness.” The role of the priests in ancient Israel was to make sacrifices for a people who sinned against God, and yet the primary qualification was not a strong sense of justice but compassion, the ability to “deal gently” with the “ignorant and wayward.” A little before this verse, the writer of Hebrews says that Jesus is our great high priest. He writes,

Since then we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast our confession. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin. Hebrews 4:15-16

Like the high priests of ancient Israel, Jesus has compassion because he knows what it is to be tempted. However, unlike the high priests, Jesus’s weakness did not lead to sin. In his book The Heart of Christ, Thomas Goodwin writes,

He that was high priest was not chosen into that office for his deep wisdom, great power, or exact holiness; but for the mercy and compassion that was in him…Now, therefore, if this be so essential a property to a high priest…then it is in Christ most eminently.1

It is this combination of sinlessness and weakness that allows Jesus to be the perfect high priest, offering perfect compassion and tenderness in a way that a high priest of ancient Israel never could.

Compassion in the Life of Jesus

We see this compassion in Jesus’s life “most eminently” in many ways throughout the gospels. He weeps at the tomb of Lazarus, heals numerous people, makes time for the most untouchable in society, and even saves a wedding party by turning water into wine. He cares for people, and people are naturally drawn to him.

But how does Jesus respond to the “ignorant and the wayward”—the specific people that Hebrews 5:2 says Jesus has compassion on? Let’s consider how the disciples, Jesus’s closest friends, treated him on the hardest night of his life, when he was betrayed by Judas and handed over to the Romans to be crucified. This was the night that Peter, James, and John would fall asleep in the garden when he asked them to pray. It was the night that all the disciples would desert him, the night that Peter would deny him three times.

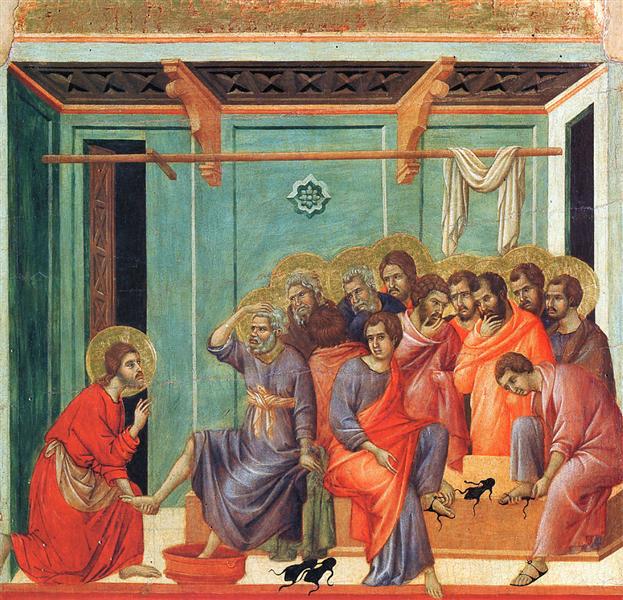

Jesus knew what the night entailed at the beginning of the Last Supper. He knew that he was going to be crucified, and he knew all the ways the disciples would sin against him in the events leading up to his death (John 13:3). However, at the beginning of the dinner, he does the most menial thing he could possibly do: “He [lays] aside his outer garments, and taking a towel, [ties] it around his waist. Then he [pours] water into a basin and [begins] to wash the disciples’ feet and to wipe them with the towel…wrapped around him” (John 13:4-5). Jesus—who would soon sit down at the right hand of God in heaven—washes the feet of his soon-to-be betrayer and wayward disciples. As Jesus explains to Peter a few verses later, this was a visual picture of his cleansing them of their sins. Knowing that within a few hours all of them would sin against Him, Jesus makes it clear that their sins will be forgiven through him.2 He demonstrates his compassion to them in a tangible way, knowing that they will soon wrong him.

After the resurrection, this same compassion undergirds Jesus’s response to his unfaithful disciples. When he sees Mary Magdalene, he tells her to “go to my brothers,” indicating that he still regarded them as brothers. While the disciples fled from him when he is arrested, Jesus seeks them out. Indeed, in John’s gospel, the first words that Jesus says to them are, “Peace be with you.” This is his response to the sin committed against him: Peace. Jesus does not require the disciples to do anything to prove that they still loved him. He simply calls them “brothers” and says they are at peace. Just as he washed their feet, they are cleansed from their sins, even those they committed on the night of the crucifixion. They are now at peace with God. They are still his disciples, and his great love for them is unchanged—although perhaps they, upon receiving such compassion, understood it better.

Compassion and Justice

Sometimes, I struggle when I feel like God is showing compassion, that tenderness, to people who don’t, in my view, deserve it, particularly when I have been hurt by someone. For example, when I was in college, I had a difficult roommate. After six weeks, my university declared me traumatized so I could move into in a dorm by myself. The psychological impact of the experience was damaging and, frankly, eight years later, I’m still sorting it out at times. For a while, the thought that Jesus could offer my roommate compassion angered me. How could she be OK, when I was so wounded? More deeply, how could God seem to think so lightly of someone hurting me?

However, when I began to consider God’s justice in light of the cross, my thinking began to change. What my roommate did to me was sin, and it was sin—her sin, my sin, our sin—that led Jesus to the cross. When Jesus was on the cross, having become sin, God did not respond to him with compassion or tenderness (2 Corinthians 5:21). Jesus died on the cross uttering, “Why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). God does not think lightly of the wrong done to me or the wrong that I have done against others—he views it with unflinching seriousness. As Dane Ortland puts it in Gentle and Lowly,

Jesus’s restraint in disciplining us for our sin] is not because he has a diluted view of our sinfulness. He knows our sinfulness far more deeply than we do. Indeed, we are aware of just the tip of the iceberg of our depravity, even in our most searching moments of self-knowledge.3

We see throughout the Bible that sin has dire consequences. In Romans 6:23, we read that the wages of sin is death. It was sin that cast Adam and Eve out of the garden, sin that stopped Moses from entering into the Promised Land, sin that led to the splitting of the Israelite kingdom, sin that put Jesus on the cross. Jesus does not gloss over sin; he dies for it. Thus, justice—the due judgment for that sin, which is death—has already been served.

When I desired God to withhold compassion from my old roommate, I was essentially saying that the cross—that justice—was not enough. However, the truth is that it is because of the cross that compassion is possible. It is because God takes sin so seriously that he did something about it, and now, he can extend us mercy. As Charles Spurgeon once put it,

I speak not lightly of thy sin, it is exceeding great; but I speak still more loftily of the blood of Christ. Great as are thy sins, the blood of Christ is greater still.4

Jesus’s blood is greater than what the disciples did to Jesus. Jesus’s blood is greater than what my roommate did to me. Jesus’s blood is greater than my pride and my fear and my sinful belief that there are some people to whom He shouldn’t show compassion.

Because of the cross, he draws near to us, we who sent him to the cross, and calls us his own. He gives us compassion, who will never deserve compassion.

How can this be?

When I think about this, my only response is: how can this be? We find an answer in Hebrews 5:2, which says the high priest “himself is beset with weakness” and in Hebrews 4:15, which says that we have a high priest “who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin.”

The high priest has compassion because he knows weakness. Even though Jesus’s weakness, unlike that of the high priests’, is sinless, he knows the utter difficulty of temptation. CS Lewis argues that Jesus is more acquainted with temptation than any of us will ever be. He writes in Mere Christianity:

Only those who try to resist temptation know how strong it is. After all, you find out the strength of the German army by fighting against it, not by giving in. You find out the strength of a wind by trying to walk against it, not by lying down. A man who gives in to temptation after five minutes simply does not know what it would have been like an hour later….We never find out the strength of the evil impulse inside us until we try to fight it: and Christ, because He was the only man who never yielded to temptation, is also the only man who knows to the full what temptation means—the only complete realist.5

Jesus knows how difficult this life is. He knows how many distractions there are. He faced every temptation, every fleshly desire that we face. He knows what we are up against.

When I hear this, my instinct is to think about all the ways that Jesus has succeeded and I have failed. How many times I have chosen to be discouraged instead of having faith, when Jesus always had faith? How could I have gossiped, when Jesus never said a coarse word? Jesus faced the same temptations, and a whole lot more than those, but he didn’t mess up as I did. Moreover, the last person that I would go to for compassion is someone who is perfect—someone who doesn’t understand what it’s like to fall again and again in his or her own mistakes. Someone who is sinless seems the least likely to give compassion. However, Spurgeon beautifully turns this way of thinking on its head. He writes,

That [Jesus had no sin] is quite true, but please remember that this does not make Christ less tender, but more so. Anything that is sinful hardens; and inasmuch as he was without sin, he was without the hardening influence that sin would bring to bear upon a man. He was all the more tender when compassed with infirmities, because sin was excluded from the list.6

It is precisely Jesus’s sinlessness that makes him perfectly compassionate to us. His compassion is complete not because he, too, has sinned, but because he hasn’t.

Approaching the Throne of Grace Boldly

When we believe that Jesus is compassionate, we can approach the throne of grace boldly because we truly believe that it is a throne of grace. We have a beautiful picture of this in the life of Peter. When Peter meets Jesus for the first time, Jesus wants to preach from his boat. After he finishes speaking, he tells Peter to cast his nets even though they hadn’t caught anything the night before. When their nets begin to break with a miraculous overload of fish, Peter’s response to Jesus is: “Depart from me, for I am a sinful man, O Lord” (Luke 5:8). Peter wants Jesus to leave—he thought his sinfulness disqualified him.

Three years later, Peter has walked with Jesus; he has gotten to know him as one of his most intimate friends and disciples. But on the night of the crucifixion, Peter fails. He falls asleep instead of praying in the garden, and he denies Christ three times. When Jesus “turn[s] and look[s] at Peter” upon his third denial, Peter [goes] out and [weeps] bitterly (Luke 22:54-62). If Peter thought he was a sinner before he ever walked with Christ, before e hever knew him intimately, how much more must he have recognized his sin and felt the pain of it that night?

However, Peter’s response when he sees Jesus for the first time after the resurrection is very different from his response that first time he felt the weight of his sin in front of Jesus three years before. There are several similarities in these accounts. He is in a boat again, and again they haven’t caught any fish. Jesus—although not yet recognized by Peter—tells them, as he did before, to cast the net on the other side, and again, the nets are miraculously overloaded.

Then, Peter realizes that it is Jesus. This time, he doesn’t tell Jesus to depart from him. he doesn’t say that he is a sinful man, even though he is probably more acquainted than ever with his sin. Instead, “he put[s] on his outer garment…and [throws] himself into the sea” (John 21:1-7). He swims to the shore to be with Jesus. He desperately wants to be near him. He could not wait to throw himself into the tender arms of our compassionate high priest. Grieved as he is by his own sin, Peter knows how Christ would receive him—and he runs to Christ.

Like Peter, let us walk with God. Let us spend time with him; let us sit at the feet of Jesus and learn. Let us let the King of Kings and Lord of Lords wash our feet. And when we sin against him, let’s throw ourselves into the sea, unashamed and boldly approaching the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need. Our Great High Priest will always receive us because he is compassionate to us.

–

About the author.

© Olivia Davis 2023, all rights reserved

Footnotes

- Thomas Goodwin, The Heart of Christ in Heaven Towards Sinners on Earth (version ebook). https://www.monergism.com/thethreshold/sdg/goodwin/The_Heart_of_Christ_-_Thomas_Goodwin.pdf.

- Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus, is the exception here. See Matthew 27:1-10.

- Dane C Ortland, Gentle and Lowly: The Heart of Christ for Sinners and Sufferers. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2020.)

- Charles Spurgeon, “The Evil and Its Remedy.” The Spurgeon Center, https://www.spurgeon.org/resource-library/sermons/the-evil-and-its-remedy/#flipbook/.

- CS Lewis, Mere Christianity. (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2000).

- Charles Spurgeon, “Our Compassionate High Priest.” The Spurgeon Library, https://www.spurgeon.org/resource-library/sermons/our-compassionate-high-priest/#flipbook/.

Leave a Reply