Last summer, I needed a gift for a friend, and the obvious possibilities—a giftcard to JCrew, a giftcard to Banana Republic, a giftcard to Target—didn’t strike a chord. Trying to think of other things my friend liked, I remembered his admiration of Hudson Taylor, a British missionary to China in the late 1800s. I enjoy drawing, and I thought I might create a portrait of him for the gift.

Before I could commit to the drawing process, I needed to find a photo of Hudson that would translate well into graphite. In addition, I wanted him to be wearing traditional Chinese clothing, which he adopted to remove boundaries between himself and the Chinese people. After combing through the entire internet, I found exactly one photo that fit the bill. However, there was a single caveat in the center of the page: a long white beard dangling over a dark robe. The individual strands were visible even in the old photograph. Despite having never drawn a white beard before, I was naively undaunted by the challenge.

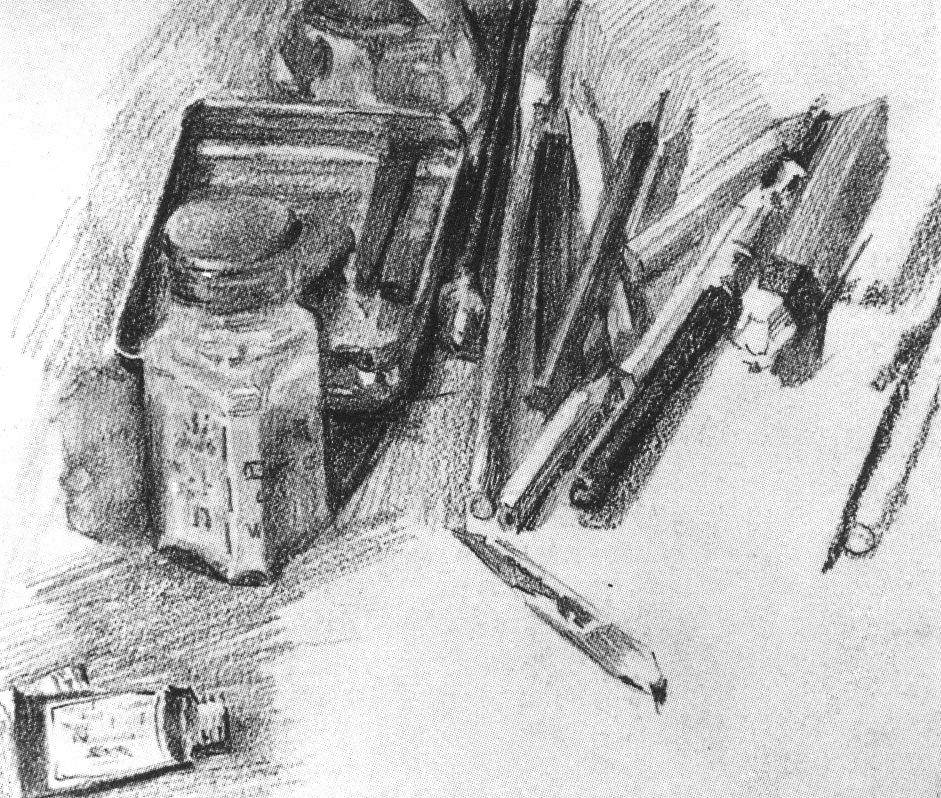

The next steps were mechanical. I cleared my coffee table, plugged in my art lamp, and clamped a piece of 11”x14” plate bristol to my drawing board. I outlined the top of the angular he sat on, his long face, and the top of his cap. I shaded the folds of his robe draped around him. Using a harder piece of graphite, I added the gentle wrinkles at the top of his nose and extending from his lower eyelid. Except for the glide of my pencils as I pushed them against the bristol, I worked in silence.

Midway through, a nebulous white cloud remained at the bottom of Hudson’s face: his beard. I tried to summon my courage by remembering that if I messed up the drawing, I could still get my friend a giftcard. I removed the blade cover of my Exacto knife. Following a wisp of hair from the side of Hudson’s cheek down to his robe, I made a shallow tear in the bristol. Then I made another tear a millimeter away from the previous, gently crossing the lines over each other with a turn of the blade. Each etching needed to be distinct and precise but follow the natural waves and flow of his hairline. One slip would ruin the drawing; a slip at the wrong angle would ruin it; digging too deeply would ruin it.

With every square inch or so of progress, I held the drawing up to my lamp, examining where the etchings were too far apart. A few times, certain areas appeared to be on the cusp of looking too rough, like the surface of an ice rink after hours of skating. I repeated the process over and over again—etching, examining, more etching. When I finally put down my knife, it was with the satisfaction that there was probably no one on Earth who had a better understanding of what Hudson’s beard looked like.

The next step was to add a layer of graphite to reveal the relief. If it worked—and I was not positive that it would—the individual strands would appear as white, contrasting against Hudson’s dark robe. I elongated the lead of a soft pencil against a piece of sandpaper. Holding it almost parallel to the paper, I brushed it like a windshield wiper over the etchings.

Much to my relief, the beard began to separate from the robe. A scintilla of hope stirred in my chest: it was working. The contrast was mild at first, but as I gained confidence, I pressed harder, and my light gray lines grew darker. The bristol took hold of the soft graphite in all the right places, and the etchings remained a clean white—just like the thin strands of hair they were supposed to represent. The cloud had become a beard.

The finish line was in sight. I added white charcoal around the irises of his eyes. Using a kneadable eraser, I highlighted the necessary places: the tips of his fingernails, the high points of the folds on his flowing robe, the tip of his nose. Then, taking a dark pencil, I found a clear place on Hudson’s robe and signed it: Olivia Davis.

As it was in the beginning, the final steps were mechanical. I wiped the simple black frame and inspected the white mat for smudges. I unclamped the portrait from the drawing board, photographed it, set it behind the glass, and closed the frame.

Hudson was finished.

That evening, I gave it to my friend, who later hung it in his office across from a world map. Serendipitously, Hudson’s eyes appeared to be looking at China, the country he served. As Hudson wrote in an 1860 letter to his sister in England,

If I had a thousand pounds China should have it—if I had a thousand lives, China should have them. No! Not China, but Christ. Can we do too much for Him? Can we do enough for such a precious Saviour?1

I mulled over this quote one day when I was at my friend’s house and studying, somewhat self-indulgently, the portrait. Why was Hudson’s savior so precious to him? Looking at the many strands in his beard, I wondered if it was because Hudson knew how precious he was to God.

My pencil-on-paper work to create Hudson’s robe and chair and eyes and his long white beard totaled 25 hours. However, it was but a shadow of the care with which God “knit him together” in Amelia Hudson’s womb (Psalm 139). As Jesus tells the disciples, “Why, even the hairs of your head are all numbered” (Luke 12:7).

When Jesus says this, he wants to encourage the disciples to not be afraid. The God who created the heavens and the earth knew each of them intimately, and he loved them and his spirit would always be with them. As Hudson, who suffered through bouts of depression, isolation, and grief, once wrote: “It does not matter where He places me, or how. That is for Him to consider, not me, for in the easiest positions He will give me grace, and in the most difficult ones His grace is sufficient.”2

In Psalm 139, David considers how God is always with us:

If I take the wings of the morning

and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea,

even there your hand shall lead me,

and your right hand shall hold me. Psalm 139:9-10

There is never a time for the Christian when God is not leading, when God is not holding you. There is not a place where God is not near. John Newton puts it beautifully:

If the Lord be with us, we have no cause of fear. His eye is upon us, His arm over us, His ear open to our prayer–His grace sufficient, His promise unchangeable. Under his protection, though the path of duty should lie through fire and water, we may cheerfully and confidently pursue it.3

Jesus’s love is so much greater than anything we can ever understand. While I gave my portrait of Hudson away, God never leaves his creation. While I got nervous many times as I drew, wondering if I would make a fatal mistake (I’ve never sympathized with the truism that there are no mistakes in art), God never gets nervous or afraid. And while I can draw a face, I can never breathe life into it.

And although I am, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer once said, a “woebegone weakling,”4 I can, amid all my insufficiency and uncertainty and fear—fear incited by something as small as drawing a strand of hair with a knife and as large as moving to a new country—turn my eyes to the God who created me, who knows me, and who is always with me. As Hudson once said: “I cannot read…I cannot pray; I can scarcely even think—but I can trust.”5 It is this trust that helps us look beyond our fears and see our God, the One to whom we, too, are precious.

–

About the author.

© Olivia Davis 2023, all rights reserved

Footnotes

- Phil Moore, Straight to the Heart of Mark: 60 Bite-Sized Insights (Grand Rapids: Monarch Books Limited, 2015), 90.

- Howard Taylor, Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 139.

- John Newton, The Works of the Rev. John Newton (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), 272.

- Eric Metaxas, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 621.

- Howard Taylor, Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 139.

Leave a Reply