“I probably wouldn’t apply for these scholarships. They are for people who want to change the world,” my college advisor said. He flipped through my résumé and then paused to make eye contact with me. Point taken. But am I supposed to change the world?

I was inquiring about applying for national scholarships, the kind that would fund a year abroad after college graduation. Now I straightened my back, as if trying to resist the shame his words draped over me. They gnawed at me as I hoisted my backpack over my shoulder and thanked him for his evidently-wasted time. What was I doing to change the world? Leaving his office, I assessed my college career, trying to stave off feelings of inadequacy.

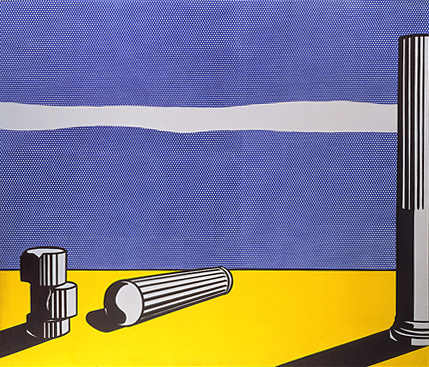

Worse than my advisor’s poor appraisal of my potential, though, was contemplating the changes the world needed, things like the end of hunger, poverty, homelessness, abuse, trauma, corruption…. How was I supposed to ameliorate any of those? Sensing my overwhelming weakness was crushing. I felt like Atlas, a Greek Titan, as he is depicted in a second-century marble sculpture known as the Farnese Atlas. He is holding the heavens on his shoulders, the result of losing a war against the Olympians. The sculpture shows him bent over, his face twisted in a painful grimace. If I were supposed to change the world, I wouldn’t look much different.

As I continued to mull over my advisor’s words, though, I realized that being a world changer, as admirable as my advisor made it seem, was not without a bit of irony. Many of the changes that we desire are often responses to another change that we, as humans, brought about. For example, we need the abolition of slavery because humans have decided to overpower and enslave each other. Our search for world changers—and our glorification of those whom we see as world changers—sometimes takes the form of a search for a savior from ourselves, from amongst ourselves. We are looking for someone to rise above our own ranks. In his book Culture Making, Andy Crouch puts it this way,

If our excitement about changing the world leads us into the grand illusion that we stand somehow outside the world, knowing what’s best for it, tools and goodwill and gusto at the ready, we have not yet come to terms with the reality that the world has changed us far more than we will ever change it.1

As the sting of my advisor’s insult wore off, I began to doubt that world changer was an aspirational identity after all. We cannot be our own saviors, which, while releasing us from the burden of bearing the weight of the world Atlas carried, also means that we need someone or something else to bring about the change the world needs. But is there something—or someone—that can bear this weight? And if we’re not supposed to change the world, what is the proper aim of our lives?

Christianity gives compelling answers to these questions, providing us both hope the world will change and purpose as we live in the world.

Hope the World Will Change

Christianity agrees that the world needs to be changed. It recognizes that something has gone wrong. As the apostle Paul writes in a letter to the early church in Rome,

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now.

Romans 8:19-22

Paul suggests that creation hopes to be “set free from its bondage to corruption.” We are not alone in sensing that the world needs change; in fact, all of creation joins us in that cry.

God not only agrees that the world needs change but also promises that such change is inevitable. In the Book of Isaiah, he promises that there will be no more weeping, laboring in vain, or untimely death, and predatory animals will not “hurt or destroy” (Isaiah 65:19-25).

These changes are so significant that God says, “For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind” (Isaiah 65:17). The apostle Peter echoes this language, writing, “But according to his promise we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells” (2 Peter 3:13). The seventeenth-century Bible commentator Matthew Henry explains,

The future glory of the saints will be so entirely different from what they ever knew before that it may well be called new heavens and a new earth.”2

God is not planning to merely change the world—He is planning to re-create it. The redemption for which creation groans is inevitable because God has promised to bring it about.

How can we believe this is true?

We can hold fast to this hope—that world change is coming—because of Jesus. His life and death are God breaking into the broken creation in a new way—a new way that is ushering in that new heavens and new earth we read about in the books of Isaiah and 2 Peter.

When Jesus died on the cross, he was allowing evil to overcome himself. As we read in Isaiah,

Yet it was the will of the Lord to crush him;

he has put him to grief…Isaiah 53:10a

Like the mythic Atlas, the world was heavy upon Jesus. But unlike Atlas, Jesus was fully crushed by the world. He let the creation he came to change crucify him. But his death made resurrection possible—and when Jesus walked out of the tomb on Easter morning, he showed that the world could not keep him crushed. The writer of Hebrews puts it this way,

Since the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise also partook of the same, that through death He might render powerless him who had the power of death, that is, the devil, and might free those who through fear of death were subject to slavery all their lives.

Hebrews 2:14

Jesus’s life and death and resurrection mean that brokenness does not get the last word. They mean that God has the power to do everything he promised in Isaiah. Thus, his resurrection gives us hope, as Peter writes, “According to his great mercy, [God] has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead” (1 Peter 1:3). We know this because Jesus was crushed by the world—and then rose from the grave, reversing death and ushering in the new creation to come.

What is there for us to do?

Because of Jesus, we don’t have to be world changers or saviors. And this is good news! If we’re honest, we might admit that we aren’t even like Atlas: The world is just too heavy for us to bear. Perhaps, in that way, we are more like Jesus in the grave than Atlas, crushed by the world and anticipating our resurrection. But where is our new life, our resurrection? John’s gospel is helpful here:

But to all who did receive him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God, who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God.

John 1:12

Christianity pulls us out of a works-based mentality that says we are more valuable if we have changed the world. It declares us children of God, a relationship that is based on a covenant instead of a contract. God will never say, “You’ve done enough” because He is not looking for us to earn anything or do anything for him. But he will say, “You are enough” because those who know him are his children (1 John 3:2, Galatians 3:26; Romans 8:14; Galatians 4:7). As Makoto Fujimura puts it,

In order for us to move beyond our utility, we need to stop regarding as the center of our being what we do to be useful and recognize that who we are in relationship to the center, God, is more important.3

Who we are is not based on what we do, but instead on who God has declared us to be.

However, God does invite us to partake in his remaking of the world, in ushering in that world change creation groans for. We see this in Paul’s letter to the church in Ephesus, “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:10). We are children of God—and he has good works for us.

And what do these good works look like? We have a few examples in the New Testament. In his letter to the church in Galatia, Paul, about to leave on a missionary journey, writes that James (the brother of Jesus), Cephas, and John asked them to “remember the poor, the very thing I was eager to do” (Galatians 2:10).

This same James wrote in another letter, “If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warmed and filled,’ without giving them the things needed for the body, what good is that? So also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead” (James 2:15-17). They care for the poor and meet people’s needs. Their identity as children of God is not a free pass to then idly wait for God to change the world but a motivation to actively join him in his work. Children of God join God in making Isaiah 65 a reality—and they do it not to be enough, but out of love for the Creator.

We don’t know the “good works” that he has for us in the future. We might do things that lead other people to consider us “world changers,” and we might not get a second glance from our college advisors. But the God who cared so much about us that he calls us his children is a God who can be trusted to do his work through our lives when we rest in him. Hudson Taylor, a late nineteenth-century missionary to China, puts it this way:

It makes no matter where He places me, or how. That is rather for Him to consider than for me; for in the easiest positions He must give me His grace, and in the most difficult His grace is sufficient. It little matters to my servant whether I send him to buy a few cash worth of things, or the most expensive articles. In either case he looks to me for the money, and brings me his purchases. So, if God place me in great perplexity, must He not give me much guidance; in positions of great difficulty, much grace; in circumstances of great pressure and trial, much strength? No fear that His resources will be unequal to the emergency! And His resources are mine, for He is mine, and is with me and dwells in me. All this springs from the believer’s oneness with Christ.4

Because of Jesus, we can partake in changing the world without the world crushing us. The specific role each of us plays does not matter because those in him are Children of God, which means that the very One who overcame the world lives within us.

An Ancient Partaker in Changing the world

A few days after that initial meeting with my advisor, someone else suggested that I consider applying for national scholarships. The suggestion encouraged me to apply despite my advisor’s dissuasion. And, six months later, the most unexpected thing happened: I received a Fulbright, an award to teach English in Athens, Greece, for a school year.

One Saturday in October 2017, I took the 550 bus from Psychiko, the Greek suburb where I lived, to the center of Athens. Then I walked to the Areopagus, a massive rock outcropping located just north of the Acropolis, the famous ancient temple dedicated to the goddess Athena, the namesake of Athens. I scaled the final steps and stood on the massive dry and dusty rock. I surveyed the remains of the ancient agora below me, linking together in my mind the bits and pieces of marble walls wedged between grass and gravel. Behind me, the Acropolis baked in the Mediterranean sun.

Nearly two thousand years ago, long before the agora was ancient or consisted of ruins, the apostle Paul stood here. Luke, who detailed the emergence of the church in the book of Acts, records this episode. After hearing Paul speak, the Athenian cultural elites brought him to the Areopagus, where the ancient council of Athens would meet. There, Paul tells them:

The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything.

Acts 17:24-25

God made heaven and earth; he does not need humans to change either one. And yet God put Paul on that giant rock to preach. God changed Paul first—a murderer became a child of God—and then Paul played a role in what God was already doing, going on missionary journeys and writing a third of the New Testament. He partook in the world change that God himself continues to usher in today.

As the sun began to cast a golden glow over Athens, I began my trek back home. The world is changing. The Acropolis Museum shines in polished glass and hosts marble ruins. By the ancient agora is a nearby Alfa-Beta Vassilopoulos.5 I walked the bustling streets of Plaka, where people take pictures of Byzantine-era churches with iPhones.

My advisor was right about me. I’m not a world changer. But I no longer think that’s a bad thing because there is someone who can bear the weight of the brokenness of the world, a true world changer. His name is Jesus, and we call him Christ.

Footnotes

- Andy Crouch, Culture Makers: Recovering Our Creative Calling (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 200.

- Matthew Henry, Matthew Henry’s Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1960), 1214.

- Makoto Fujimura, Art + Faith: A Theology of Making (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 94.

- Dr. and Mrs. Howard Taylor, Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission: The Growth of a Work of God (London: Morgan & Scott, LD., 1919), 176.

- AB Vassilopoulos is one of the major modern grocery chains in Greece.

Leave a Reply